Fire Retardant Additives for Thermal Runaway

Expandable graphite and Quarzwerke minerals can be used to enhance flame-retardant systems for EV safety.

Global adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) is accelerating however, range anxiety remains a barrier for motorists in Western Europe. In response, EV manufacturers opt for fitting newer models with increasingly larger batteries. The management of the associated fire risks of such energy-dense systems is becoming more challenging and complex. Fire safety, in this context, depends on a combination of heat insulation, gas barrier properties, and char formation; three functions that must be supported by the right flame retardant (FR) system.

One of the most critical hazards to passenger safety is thermal runaway, a self-propagating reaction within lithium-ion batteries that can lead to violent fires or explosions (Figure 1). Manufacturers are racing to design EV components (enclosures, gaskets, insulation materials etc) that offer adequate fire protection under these extreme conditions.

Figure 1: Without flame retardancy, lithium-ion batteries are subject to thermal runaway, which can produce extreme vehicle fires.

Preventing thermal runaway starts with selecting the right materials. Key polymer systems used in EVs include a range of engineering thermoplastics and thermosetting resins such as acrylics, epoxies, polyurethanes, and silicones. Each offers unique properties for sealing, potting, or housing battery components, but all are vulnerable to degradation during a thermal runaway event.

To protect the EV’s passengers, polymer components must maintain their structural integrity during combustion. This is especially important for the interfaces between the battery packs and the passenger cabin – any potential failure should always be in the direction away from human lives. The formation of an insulative, mechanically robust char is considered particularly important to protect passengers against thermal runaway.

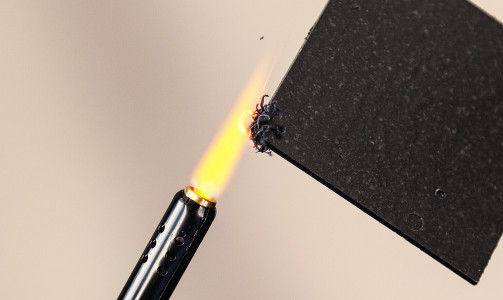

The traditional tests used to quantify the flame retardancy of compounds such as cone calorimetry, UL94, and limiting oxygen index (LOI), are being supplemented by those combining combustion and mechanical stresses, such as the Torch and Grit test. The latter involves the intermittent burning and blasting of components with hard alumina particles to challenge the structural integrity of the char layer. Only the toughest char layers survive. This process can be seen in the video below.

Video 1: The Torch and Grit test involves intermittently burning and blasting components with hard alumina particles to challenge the structural integrity of the char layer.

To create strong and cohesive char structures, formulators are turning their attention to inorganic minerals that undergo ceramic sintering during combustion to form materials with porcelain-like hardness.

Several ceramifiable chemistries are available. These include silicas (quartz flours), calcium silicates (e.g. wollastonite), and aluminium silicates (e.g. kaolin, mica, and feldspar). All of these fillers readily undergo ceramic phase formation, but contribute to the char in different ways.

SILBOND Silica results in hard ceramic layers with high flexural strength. TREMIN Wollastonite is best at retaining the initial shape of the composite. The needle-like morphology of wollastonite helps to provide a ‘frame’ structure to support the expanded char. Aluminium silicates such as MICROSPAR Feldspar provide glass-phase fluxing oxides (e.g., K₂O, Na₂O) that lower the sintering temperature of the minerals. This aids in consolidating the ceramic layers and to fill cracks that may form as the material loses mass during combustion.

We illustrate with an example from the academic literature. Figure 3 contains a snapshot from a recent study of mineral-containing polyethylene composites exposed to extreme temperatures. Samples were created using a combination of polyethylene, glass powder (as a main fluxing agent), and of one of the three types of ceramifiable mineral filler (40 wt%). Figure 3 shows the composites before (a) and after (d) ablation at 1000 °C. The control sample, containing only the polymer and glass powder, completely melted at this temperature. Each of the filled systems survived (with some notable differences between the mineral chemistries, each offering its own advantages beyond the scope of this article).

Figure 2: Composite samples before and after ablation at 1000 °C, each containing a ceramifiable mineral filler at 40 wt%. Reproduced from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0272884222041487#bib28

No single flame-retardant technology is a silver bullet, and formulators must balance intumescence, thermal insulation, and char reinforcement to develop high-performance flame-retardant systems for EV materials.

In that context, the use of expandable graphite in combination with mineral fillers presents an interesting example. Expandable graphite (EG) from LUH is a well-established mineral flame retardant which is highly effective at forming a voluminous intumescent char. EG is excellent at slowing flame spread and reducing the heat release rate. However, its expanded structure can be mechanically fragile or prone to collapse under heat and pressure - particularly in vertical or load-bearing applications. This can be addressed to some degree by selecting the appropriate grade of expandable graphite, for example, by tuning the particle size and expansion pressure.

An emerging approach is the deployment of expandable graphite in combination with synergistic minerals that reinforce the voluminous cavity created during expansion of the graphite. For example, a recent study in Construction and Building Materials (Ahmad et al., 2019) investigated a series of coatings containing expandable graphite reinforced with wollastonite and aluminosilicates. The addition of mineral fillers resulted in a noticeably dense and compact ceramic char (Figure 4). The formation of dense ceramic domains was attributed to wollastonite’s acicular structure and the reinforcing action of aluminosilicate minerals (Figure 4). Importantly, the addition of mineral fillers improved the fire protection of the resulting char layer (which was measured in function of the temperature of an underlying steel substrate). The minerals also lowered the thermal conductivity of the char layer, which benefited the low flame penetration. [Ahmad et al., Constr. Build. Mater., 2019, 228, 116734]

Figure 3: Reproduced from [Ahmad et al., Constr. Build. Mater., 2019, 228, 116734]. Left: inner char with cracked hexagonal voids (0% filler). Right: inner char structure reinforced with wollastonite and aluminosilicate (4%) with a noticeably denser char structure. SEM images taken at equal magnification.

Thermal runaway mitigation in EV applications demands advanced flame-retardant systems that actively preserve the structural integrity of components under extreme conditions. In this article, we demonstrated how mineral fillers such as aluminosilicates, wollastonite, and feldspar can work synergistically to deliver the necessary mechanical reinforcement in flame-retardant systems. These minerals can be combined with workhorse intumescents such as expandable graphite.

By carefully formulating combinations of these additives & fillers, materials engineers can develop porcelain-like, load-bearing ceramic chars that defend EV components against catastrophic fire propagation during thermal runaway.

Please get in touch to explore our range of flame-retardant additives designed to meet your processing and performance needs.

Expandable graphite and Quarzwerke minerals can be used to enhance flame-retardant systems for EV safety.

High Temperature Expandable Graphite from LUH is able to be used in thermoplastics without expanding during the extrusion process.

Micaceous Iron Oxide (MIO) is a naturally occurring iron oxide used in protective coatings due to a lamellar/platy morphology that allows it to form a barrier towards the ingress of water.